Been to meet academic girlfriends for a museum day and really enjoyed it. This Christmas has been hard, and now things are picking up a little I badly need to enjoy myself a bit. I’ve treated myself to a new sweatshirt – it’s pale blue and has ‘Reading for Pleasure’ embroidered on it. There’s a constant refrain of self-improvement about at this time of year and I’m reacting badly to that. Sometimes what you need is actual pleasure – whether it’s as trivial as meeting friends, a new jumper, time to read a good book or to go to a museum.

When I went last week to the British Museum’s Legions: Roman Army museum exhibition most of the visitors did in fact seem to be enjoying themselves. It wasn’t very busy and I stepped out of the way of a youngish white couple who were politely waiting for me to finish looking so he could take a selfie of himself with a bust of Emperor Augustus near the entrance of the exhibition. No shade on them – we had a pleasant chat and we all politely agreed there was quite a resemblance between him and Augustus. While he took his selfie however I asked his partner if she thought she’d be taking a selfie too.

“Well if I find someone who looks like me,” she paused. “But that’s not very likely is it really?” and we laughed, agreeing that it was not. Our laughter had a slightly uncomfortable note as we both recognized who the exhibition was about and that it wasn’t us. She had in fact the expression of a partner who was happy to accompany but was herself perhaps not so interested. They both seemed lovely and I am sure none of us harboured any illusions that he was actually anything like a Roman emperor; that he wasn’t was part of our shared joke. There seemed to be plenty of humour in the museum to engage children’s imagination too – Rattus, a supposed recruit (and annoyingly obvious derivative of Minimus, the well-known Roman Army mouse) told his story with panels and costumes to try on and fun things to do.

The exhibition had many absolutely stunning exhibits that I did ooh and ahh over. But I’m an archaeologist and as I walked round this means I noticed very much the demographic of the visitors – they were mostly middle-aged white men. I visited during the day, which might explain the visitor age but not in a city as diverse as London, the maleness and whiteness. I found myself thinking about my conversation with the young woman and how the exhibition’s portrayals of women made it not the same fun experience that it clearly was for most of the men there.

Most glaring was the lack of perspective on the few women who were included in the exhibition. Arguments about things being ‘just how it was’, don’t wash when you highlight Terentianus’ request for familial consent to buy an enslaved woman and don’t include anything about the woman herself. How things were for her is a part of ‘just how it was’ in the Roman army.

On a more than technical point Terentianus is most probably intending to purchase an enslaved woman in order to free her to become his wife. This is what the Palmyrene Barates probably did with Regina at South Shields, whose tombstone is in the exhibition but the parallels were more hinted at rather than examined. On an accuracy point the exhibition claims Barates is a ‘soldier’; he could have been but as scholars and museums have repeatedly pointed out, the inscription does not say that. There was a Roman soldier called Barates at Hadrian’s Wall who put up an inscription at Corbridge – but it’s a common Palmyrene name and they’re probably not the same man.*

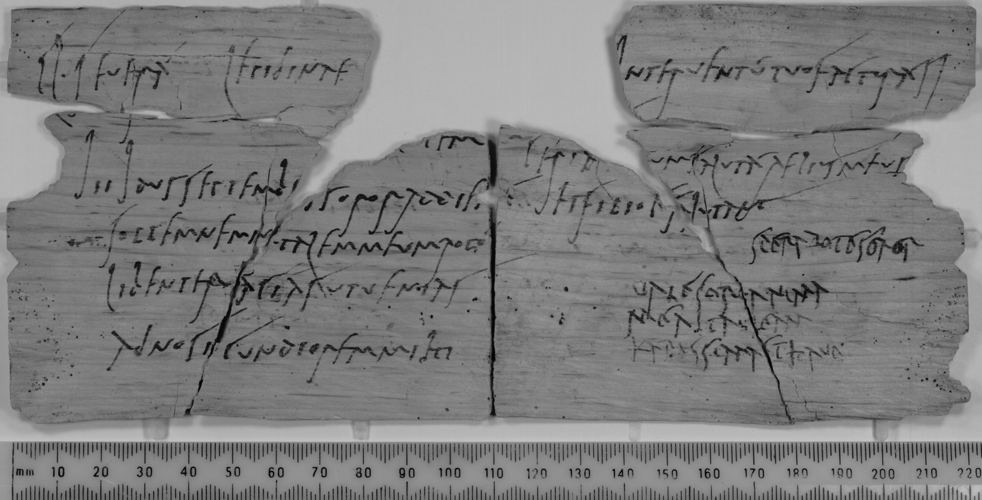

I was expecting to enjoy more the display about the women known from around Hadrian’s Wall, in particular finding some solidarity with Claudia Severa, whose insistence on the importance of her own pleasure was something I was in the mood for. Claudia Severa probably had little choice when she accompanied her husband, a Roman auxiliary unit commander, at the end of the first century to a fort somewhere near the later Hadrian’s wall. Faced with the religious solemnities of her birthday however she writes to invite the commander at Vindolanda fort and his wife, Sulpicia Lepidina to visit her and her husband.

ad diem sollemnem natalem meum rogó libenter faciás ut uenias ad nos iucundiorem mihi

“for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make [the day] more enjoyable for me.”

The exhibition label said that it’s the earliest woman’s Latin handwriting known, suggesting that it was rare for a woman to be writing at this time. This is not true. It is the earliest Latin handwriting by a woman TO WHICH WE CAN ASSIGN A DATE BECAUSE IT CAME FROM A MODERN EXCAVATION. One of the most important things about this letter is that it suggests how mundane it was for these officers’ wives to be writing letters, including some ability to use an ink pen. The Empress Julia Domna (whose militaristic wig choices were discussed in the exhibition) was in fact said by Dio to have managed her son the Emperor Caracalla’s letters and petitions. Dio says that when writing to the senate, Caracalla included Domna’s name along with his own and the names of the legions, stating that she was well. Not very different perhaps to the greetings and invitations being conveyed between officer households by their wives. Other Vindolanda women’s letters could have been included too – Paterna wrote to Lepidina promising to bring either enslaved girls free from fever or a remedy for fever, again saying something about these women’s roles.

The museum labelled Severa’s letter a ‘Birthday party invite’ and emphasized the party element. This isn’t actually quite what the Latin says, which uses sollemnis, and as Judy Hallett notes in her critical edition of this letter, implies a religious celebration. A couple of men reading the museum’s explanation however sniggered rather nastily as they spluttered at the idea of these silly women’s ‘birthday party.’ Their rampant misogyny didn’t really give me a good time, and the exhibition context felt more supportive of them than me. This isn’t a formal academic review – there’s much more I want to discuss about non-combatants, legionary bases (strangely absent), migration and reception especially of the red hanging banner imagery and fascist history – but sometimes you need to say what you want to say, including how you feel. Severa thought her pleasure was important enough to use as a reason to persuade an officer and his wife to visit. I think mine counts too when it comes to visiting a museum.

Oh and go say ‘hi’ to Minimus. He seems a bit left out to me. www.minimuslatin.co.uk

Pingback: Archaeology 2024-02-15 – Ingram Braun

Pingback: Behind the tweets at the British Museum | Dr. Claire Millington

Now imagine how interesting and unique an exhibition could have been that focuses on the perspective of families, service-providers and other non-combatants that accompanied a roman army on their years-long journey!