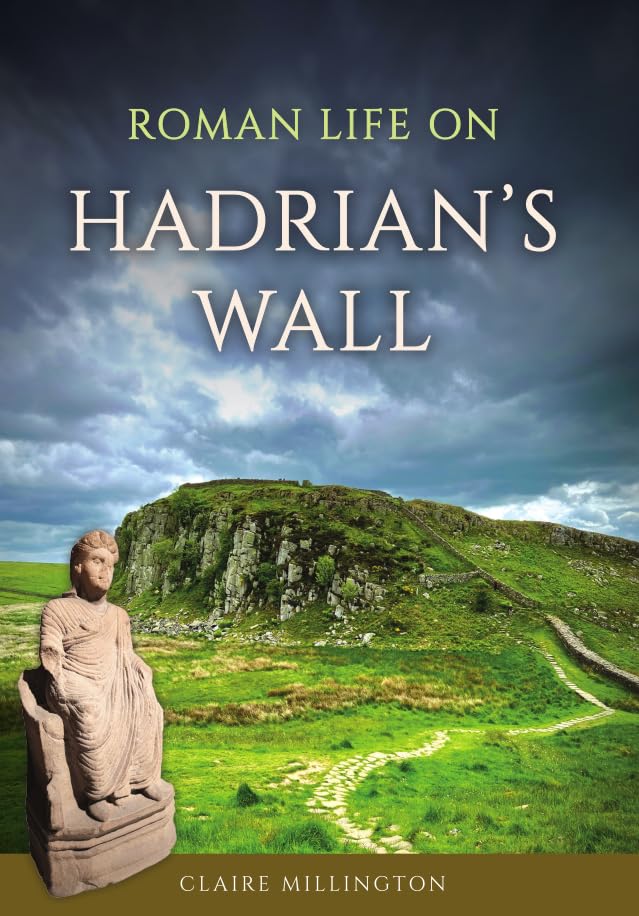

I’ve got my proofs for ‘Roman Life on Hadrian’s Wall’ back and am working on a proposal for another book about Romans, so how to write history books is something that is in my head a lot at the moment.

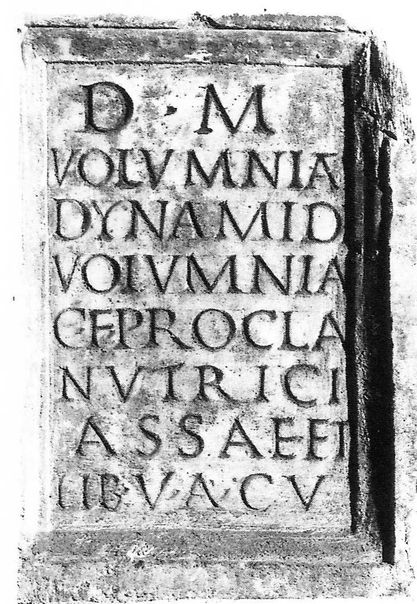

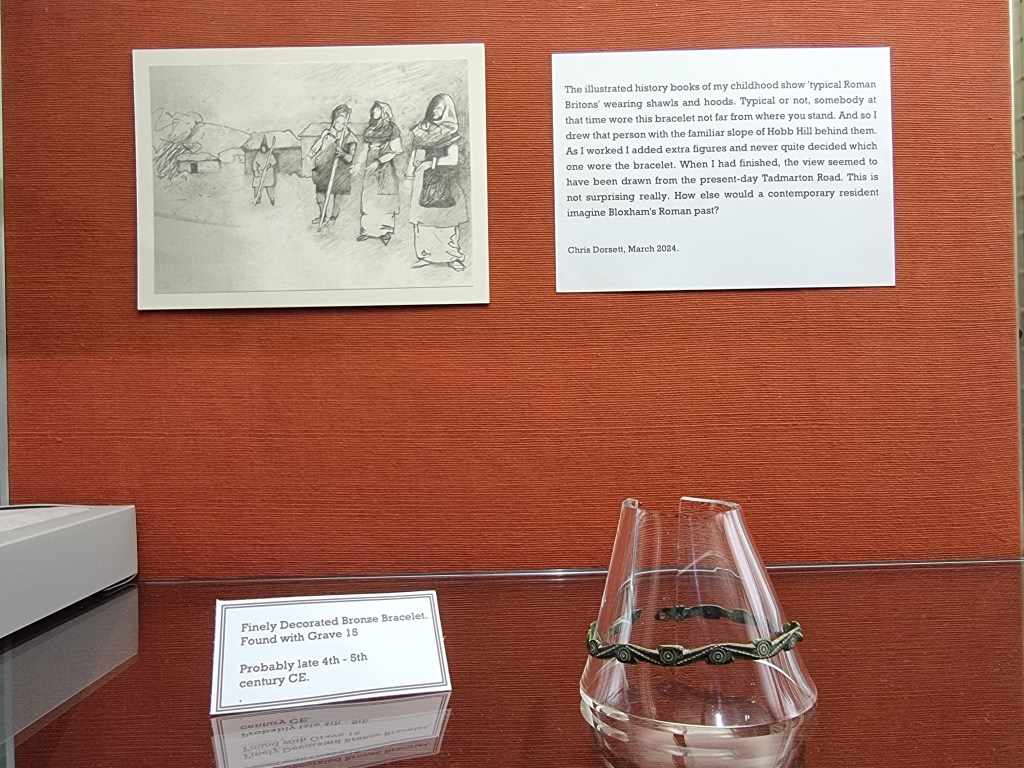

One big thing I’m thinking about are the differences between writing for academic readers and for general readers, that is people who are interested in history but not academics. Academic archaeology writing is usually very cautious. It’s more like a conversation between a group of colleagues who are remembering previous conversations and thinking what other people have said and respecting their expertise. There are questions that people have explored and drawn conclusions about, which can be re-opened or not, but fundamentally academics are interested in how the work of experts fits together, rather than the particular stories that are being told. The idea is generally to establish what are facts and discuss theoretical models that are the ways the facts might fit together. One of the purposes of this is to stop what are basically myths being passed off as history, because the evidence has either not been sufficiently understood or modern viewpoints are getting in the way. The example I most often deal with is the idea that there weren’t many civilians, and especially not women and children, with the Roman army, which is a myth that sprang up largely due to the interests of the soldiers from the eighteenth century onwards who studied the Roman army. It’s part of why I wrote ‘Roman Life on Hadrian’s Wall’, to put the spotlight on these people in an attempt to say something about their lives and importance to Roman imperialism.

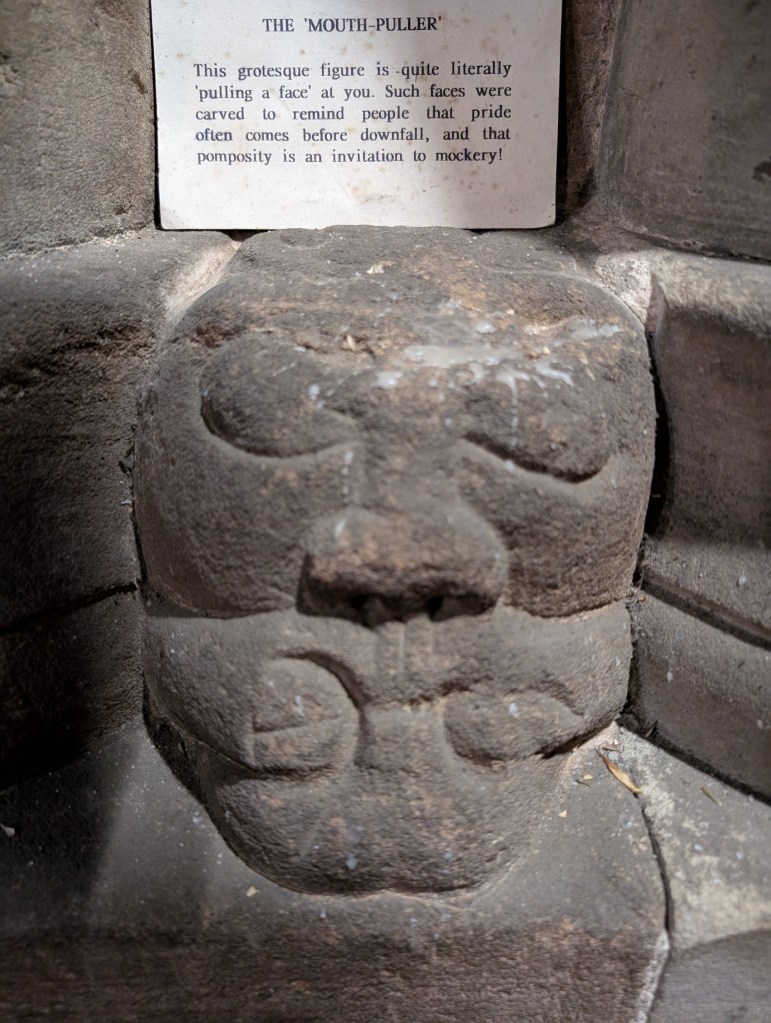

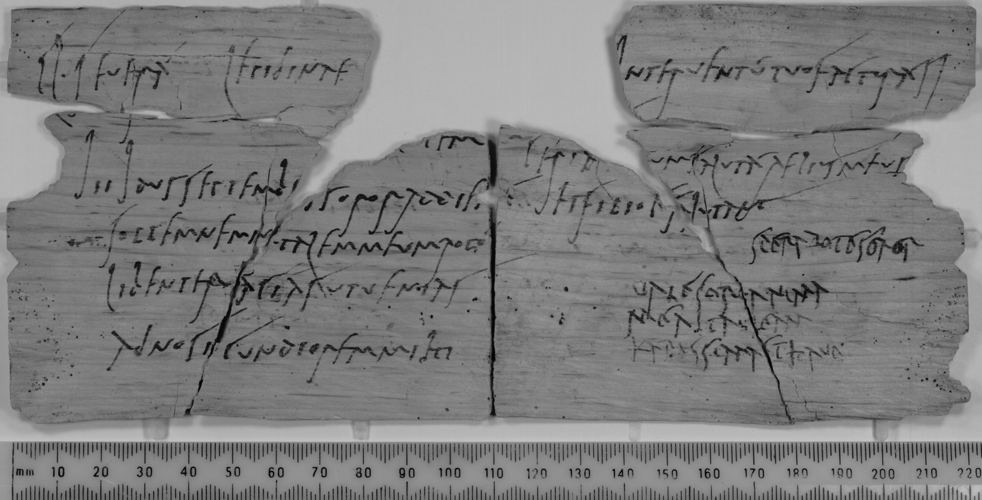

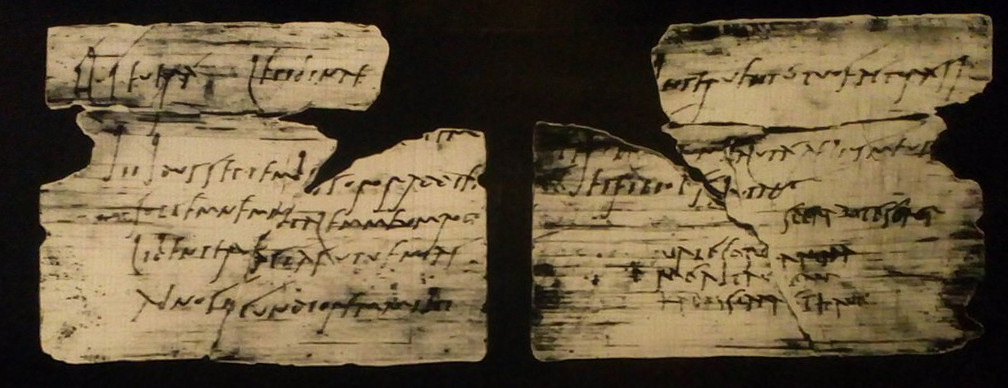

There is a very big difficulty however in trying to understand people in the ancient past. We don’t have much writing from people who weren’t free men with lots of money. This means that we don’t directly have the viewpoints of most people who lived in the past to tell us what their lives were like. This is of course what people now are most often interested in. What was it really like? What did people think and feel? Modern stereotypes tend to cause confusion here. Ideas about childhood, for example, change a lot. When are people actually grown up? Modern culture keeps examining people’s brains and declaring adulthood to be older and older – apparently adolescence now continues into your thirties. By that age Roman men could have had several army promotions and women might have been married several times as well as having raised to adulthood the oldest of their children. Writing for more generalist readers means being aware of modern assumptions as well as not dragging readers into the academic questions that are fundamentally important to the facts. Putting this all together though, means it’s possible to avoid unrealistic ‘how it was’ stories and instead to write something new, accurate and interesting about the past, which is really what I’m trying to do.

You must be logged in to post a comment.