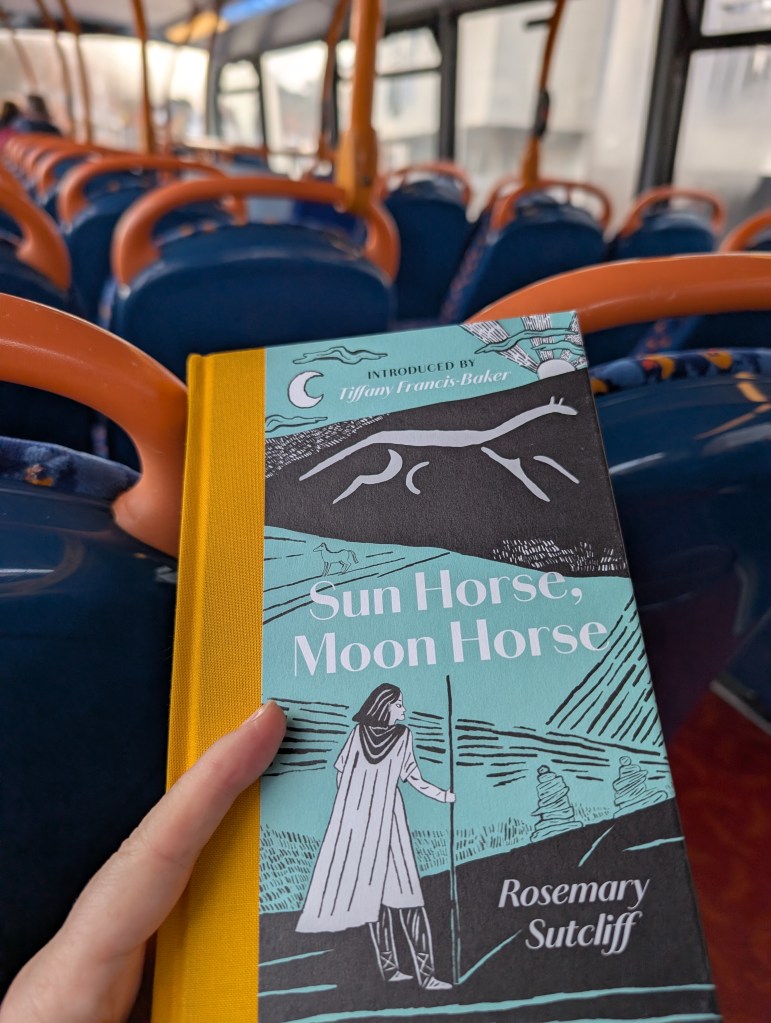

One of the difficulties in writing for children about prehistory is that, judged by modern expectations, the ancient world was brutal. The problems of this are stark in Rosemary Sutcliffe’s ‘Sun Horse, Moon Horse’, a book that I didn’t read as a small child, although it was first published in 1977. Manderley press has given it a truly beautiful new edition and this week I took it to read on the bus.

The forward by Tiffany Francis-Baker addresses these problems directly: “Exploring the lightest and darkest parts of life, and the cross-over between myth, fantasy and reality, Sun Horse, Moon Horse does not shy away from serious, complicated themes like invasion and diaspora, power and violence, sacrifice and survival, as well as the more gentle themes of friendship, family and community, all set against the beautiful backdrop of the natural world. Above all, this story is a reminder of the wisdom and resilience of children in a world that can be far too quick to dismiss the voices of the young.”

This seems to me to say it about right: the world is not a safe space for adults, however much we may wish it otherwise. It is frequently horrifying that children grow up in this world that we have made, and at least in the UK, adults can have a very natural urge to overprotect children. But children are in this real world and as they grow up we must equip them to deal with realities. Giving children books where the story – fictional or not – acknowledges the horrors but keeps the focus firmly on important things like friendship, family and community, gently suggests ways of coping. Sutcliff’s writing is terrific, and in her own preface she quietly warns a young reader that “in a way, my story has a happy ending”. Both these introductions act as content labels, and I think this is enough. Sutcliff’s introduction is very short and let’s a child decide whether or not to continue reading. Francis-Baker writes a longer introduction that a child would probably skip; like the expensive hardback edition, this seems intended towards an adult. Either way, there’s enough of a description for a reader to decide if it’s for them.

I’m not sure that this viewpoint is one that will find much favour; I suspect it may be adult unease at the book’s content (human sacrifice) that means its is less well known than her Eagle of the Ninth trilogy. Or it might be just that adults decided that this book wasn’t suitable for me as a child. My mother tells of the nightmares and screaming that followed an infant school Easter assembly about the crucifixion. At seven I probably was too young, although I have absolutely no memory of the event and it doesn’t seem to have done me harm learning about it then. Terry Pratchett (whose chalk horse I shall come onto in a minute) held similar views. He criticised schools for banning books because the word ‘witch’ was in the title, paraphrasing G.K. Chesterton: “The objection to fairy stories is that they tell children there are dragons. But children have always known there are dragons. Fairy stories tell children that dragons can be killed.”

Even so, pitching a book to a children’s publisher that ends with a human sacrifice (as does Sun Horse, Moon Horse) sounds daunting. I think as a young child I would have found the ending deeply affecting, although probably no more so than the deaths of horses in Elyne Mitchell’s ‘Silver Brumby’ series, over which I wept copiously. Sun Horse, Moon Horse is a terrific book that deserves to be read for the sheer imagination with which it conjures a prehistoric world and how the people who lived in it might have perceived it.

Sutcliff’s book is not perfect. Lubrin is dark skinned, of mixed ethnicity, which Sutcliff (writing in 1977) presents as a stigma to be overcome. His mother cries because of his “darkness” which comes from her side of his family. His racial difference is linked to his creativity and his ultimate self-sacrifice is for a community where he was bullied for both. Although Sutcliff does offer nuance – Lubrin has a variety of different responses and relationships within his society – when read in 2026 the book is marred. Even so, it envisions humane and sympathetic views about understanding human life at different times and places, and is written exceptionally well. Flaws aside, I loved it.

Sun Horse, Moon Horse also made me wonder again about Terry Pratchett and whether he had read Sutcliffe. The central part of the plot is the making of the Uffington White Horse by an artist, Lubrin Dhu. Lubrin has in fact invented drawing, it is not something that his society does (which is not historically accurate, but fiction doesn’t have to be). He solves the problems of how to make a huge figure that he can’t see the whole of, and with his community he re-makes it three times to get it right. In the end:

“One long, lovely, unbroken line swept the whole length of the arched neck and back and streaming tail…the head had something of a falcon’s look about it; the two farthest legs did not join the body at all. None of that mattered. He was not making the outward seeming, up there among the drifting cloud-shadows and the lark song. He was making the power and the beauty and the potency of a horse, of Epona herself, though his conquerors would never know it.”

This is really similar to Pratchett’s description of the horse in A Hat Full of Sky:

I meant why do they call it a horse? It doesn’t look like a horse. It’s just . . . flowing lines . . .”

. . . that look as if they’re moving, Tiffany thought.

It had been cut out of the turf way back in the old days, people said, by the folk who’d built the stone circles and buried their kin in big earth mounds. And they’d cut out the Horse at one end of this little green valley, ten times bigger than a real horse and, if you didn’t look at it with your mind right, the wrong shape, too. Yet they must have known horses, owned horses, seen them every day, and they weren’t stupid people just because they lived a long time ago.

Tiffany had once asked her father about the look of the Horse, when they’d come all the way over here for a sheep fair, and he told her what Granny Aching had told him when he was a little boy. He passed on what she said word for word, and Tiffany did the same now.

“’Taint what a horse looks like,” said Tiffany. “It’s what a horse be.”

Both books are inextricable from the chalk downlands of southern England where they are set and it is obvious that both writers loved these landscapes. Bleakly though, adults are wreaking harm on these chalklands – by changed climates, agricultural chemicals, ripping out hedgerows, bad development, tipping sewage into rivers, invasive plants, and pollution. Our children will be made responsible for the consequences. The very least we can do is to give children books that support them both in coping with big and difficult things as children, and in helping them to become grown ups who can deal with responsibilities, perhaps especially those that are not their fault. I think Pratchett and Sutcliff’s books are on that list.

You must be logged in to post a comment.