Been thinking about numbers lately as several friends have reached the half century mark, five sixths of the three score years that denotes old age, or once did. Ten years then left to the expectation of a lifespan.

Threescore and ten I can remember well – Old Man, Macbeth.

Except that lifespan has increased in the UK and other wealthy countries, as long as you’re not homeless on the streets, or having your telomeres, the endstops of your chromosomes tattered away by racism, or through many other means being spun away before your time. The reporting this week of the COVID inquiry brought back to focus the 23,000 people who died unnecessarily because of the revolting inability of politicians to make good decisions during a pandemic also shortened people’s lives and expectations. That number is not exact, as the relatives of those who died will be able to tell you with much greater precision.

This ideal of longevity itself is long-lived, as is really clear from Roman tombstones, where ages are only usually included to make a point. The borne unbearability of children’s deaths, recorded with precision of months and days, even though half of Roman children did not survive their childhood. Little Ertole was only four years and sixty days when she died. Her father Sudrenus said on her memorial that she was officially called Vellibia and was a happy child.

Ages are also included on gravestones for very old people. Sometimes these are accurate. A person who reached 80 years and five months was mourned by their family in Brougham Cemetery, just outside the fort and settlement at Old Penrith. Their name may be lost to time – the inscription is damaged – but the exactitude of their age survives.

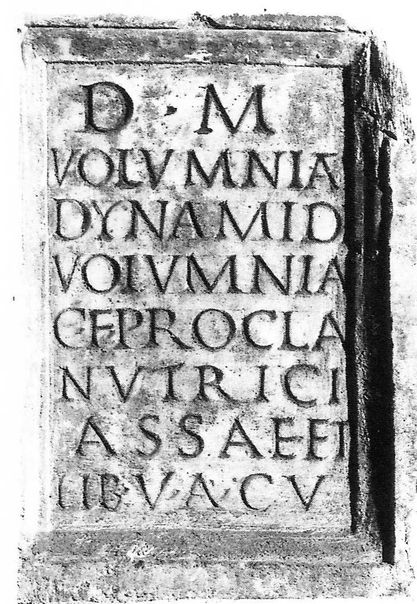

In most cases though these great ages were fantastical, such as the ‘100-year old’ legionary centurion Julius Varens whose wife Secundina and son Martinus commissioned a monument for at Caerleon. Was he really 100? Probably not, the idea was to celebrate the great age that Varens had achieved. There are even more improbable tombstones: Volumnia Dynamis, a freedwoman who was a dry-nurse, was said to be 105 when she died, and the stele of Gaius Oius Secundus in Spain says he was 125. Old age was particularly plentiful in Spain if we are to believe these stones’ stories. We shouldn’t though, it’s very noticeable that ages are rounded up to the nearest five years. In fact if you compare the number of Roman inscriptions with ages ending ‘5’ or ‘0’ against what you’d expect the number to be of people aged say, 25 rather than 24 or 26, you find that this is true. A lot of adult Romans either didn’t know or particularly care how old they were.

The idea that age can tell you something about what a person is worth underlies what is written on all of these stones. These are the voices of survivors who mourn their dead in their own society. The bodies of those dead sometimes tell a different story.

A skeleton of a Roman-era woman from The Mount at York showed that she had been killed by having her face smashed in so hard that her teeth were broken at the roots, as well as several stab wounds to her spine. This is a pattern of face-to-face ‘overkill’ recognisable today as elder or familial abuse, where the assailant knows the victim, even if by today’s standards she was only around 46 years old. Two older women at Watersmeet in Cambridgeshire had suffered badly from arthritis and one had a fractured forearm that had not healed. They were not included in the main cemetery and were possibly buried while still alive. There was certainly no evidence of care taken over these disabled women’s funerals. Another woman at Bourne in Lincolnshire had simply been dumped in a ditch with little ceremony or care. She was aged over fifty and the site was industrial; and I suspect she may have been enslaved worker there with few kin to ensure her proper care.*

People in the Roman world were also brutally evaluated as slaves, and their age and gender were the two factors that made up most of that value. An imperial edict from 301 CE documents the maximum prices permitted for enslaved men and for enslaved women. At 40 the value of both men and women began to fall, with the biggest fall for both coming after 60 years old, when death would be expected.

| Price in denarii | ||

| Age | Men | Women |

| 0 to 8 | 15,000 | 10,000 |

| 8 to 16 | 20,000 | 20,000 |

| 16 to 40 | 30,000 | 25,000 |

| 40 to 60 | 25,000 | 20,000 |

| 60+ | 15,000 | 10,000 |

This kind of evaluation was also one of the themes of the pandemic, that only people who were old, or who had ‘underlying conditions’ would be killed by COVID. These were people considered to have less value, and to be a drag on the economy. A supreme court judge, Lord Sumption, even felt comfortable telling Deborah James, a woman whose cancer was terminal that her life was of “less value“, because she had fewer years ahead of her than did his grandchildren. His argument was crass, largely based on economics, what will we pay to support these older people? What will we pay for children? What are people worth?

Numbers seem more and more to be being used to evaluate people. How many steps in a day, heartbeats in a minute, fat cells in a body. Did you in fact bring on yourself your own poverty and sickness, the weight you place on other people? Is your body in fact worth it? Metrics for producing a healthy young workforce, and selling gym memberships and ‘health’ supplements. Only if you can measure can you sell it. We’re at a point where we have wondrous new technologies, computer programs that can calculate probabilities and find patterns, solve problems if we ask them carefully and give them good information. There’s plenty of wealth in this world too, what we seem to lack is imagination and a better view of human nature.

Romans mostly didn’t only not care exactly how old people were, and they said that both children and very old people should be celebrated (even if they also didn’t live up to those ideals, and there were plenty of wealthy men with big platforms to say that children shouldn’t be mourned over-much). Romans also invented birthdays for ordinary people. Until then it was only cities or the birth of monarchs that were occasions for celebration. With Romans came the idea of celebrating everyone, exchanging gifts and having parties, even writing poems and books about birthdays. How old you were didn’t matter: the famous birthday invitation sent by Claudia Severa to her friend Sulpicia Lepidina gave the date, but didn’t even mention her age. Maybe we could think more like that too.

*Gowland, R. L. (2016). That ‘tattered coat upon a stick’ the ageing body: evidence for elder marginalisation and abuse in Roman Britain. In L. Powell, W. Southwell-Wright, & R. L. Gowland (Eds.), Care in the past : archaeological and interdisciplinary perspectives. Oxbow Books.

You must be logged in to post a comment.