Shortened days and storm-blown power cuts call for stories, and the loss of my uncle, my mum’s step-brother, echoing the loss last year of Steve’s dad has put me out of tune for the familiar schmaltz of Christmas Victoriana. But stories demand nothing but that I read with them; no need to rouse from sugar-slugged exhaustion to pin lights or wrestle the plastic tree down from the loft. Deeply in need of rest I am restless; returning to see friends in my hometown I revisited St Chad’s church, and find solace in Gawain’s new year’s tale, another Midlands story.

St Chad’s was built in the twelfth century and is now rather overwhelmed by its thoroughly ugly modern neighbours on Stafford’s Greengate St. Behind its pretty Romanesque front, the work of George Gilbert Scott, it is filled with exquisite Norman stone-carving that after the church’s ruination was preserved by being plastered over in the seventeenth century, the plaster then being removed in restorations a hundred years later. So well preserved is this carving from the ‘ruined church’ in fact that my curmudgeonly archaeologist’s suspicion is that some of it was re-cut by the Victorians. On checking, I find I’m not the first to suspect this, although I’m happy to accept the opinions that the designs remain genuine enough.

Over these stones dragons chase, twisting wyrms that call attention to the name of the church’s founder, Orm, whose inscription sits above a pillar.

“‘Orm Vocatur Qui Me Condidit’ The man called Orm built me.

Orm is probably the local landowner, Orm le Guidon, about whom local myths have sprung up including that he was a knightly crusader, although the facts do not seem to fit and perhaps should get in the way of embroidering a good story.

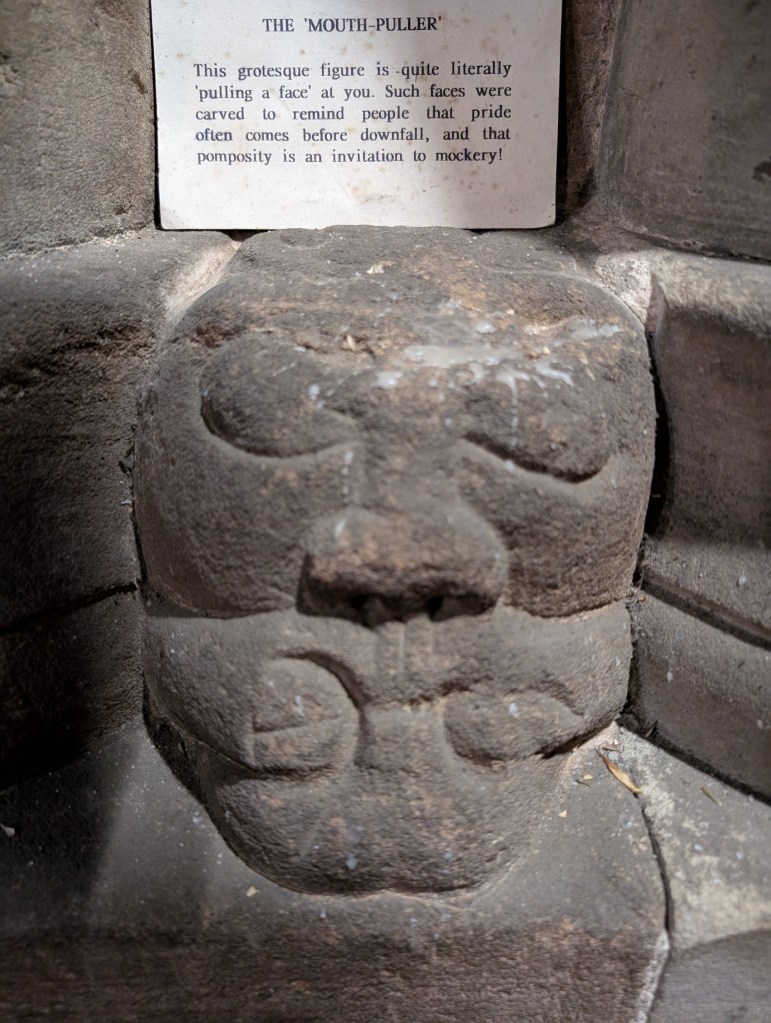

The extraordinary stone cutting however goes on and on around the church – the font, voissoirs with wonderful ‘beakheads,’ the ‘mouth-puller,’ a strange figure akin to a Sheela Na Gig, and two carvings of a ‘green man.’

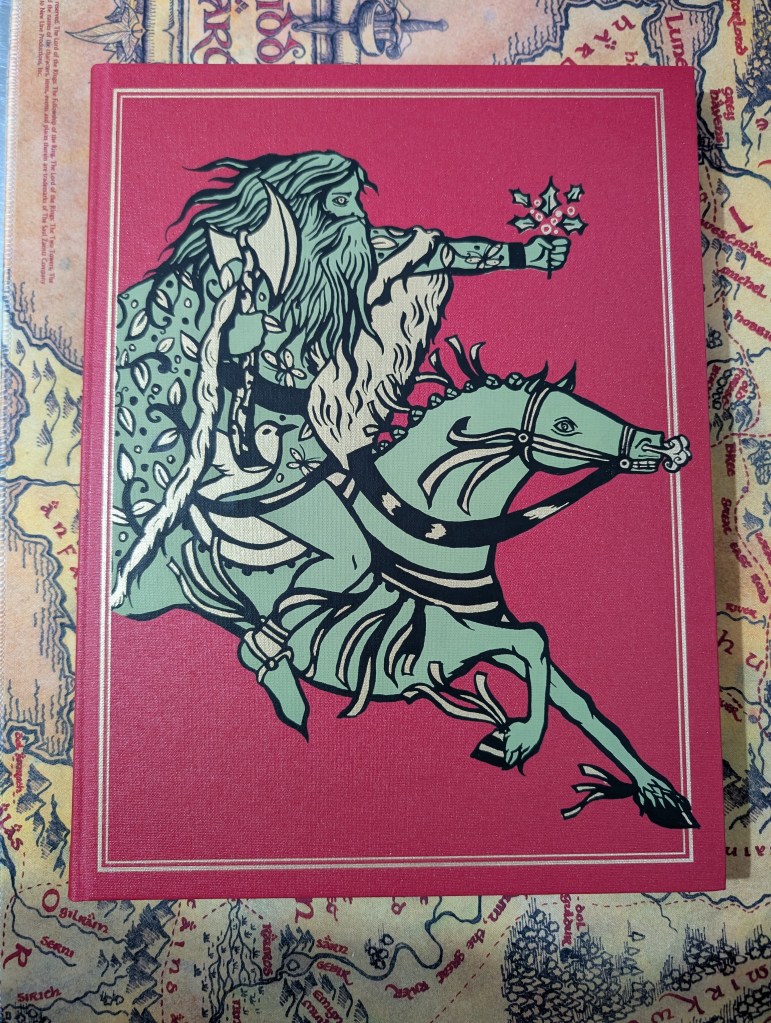

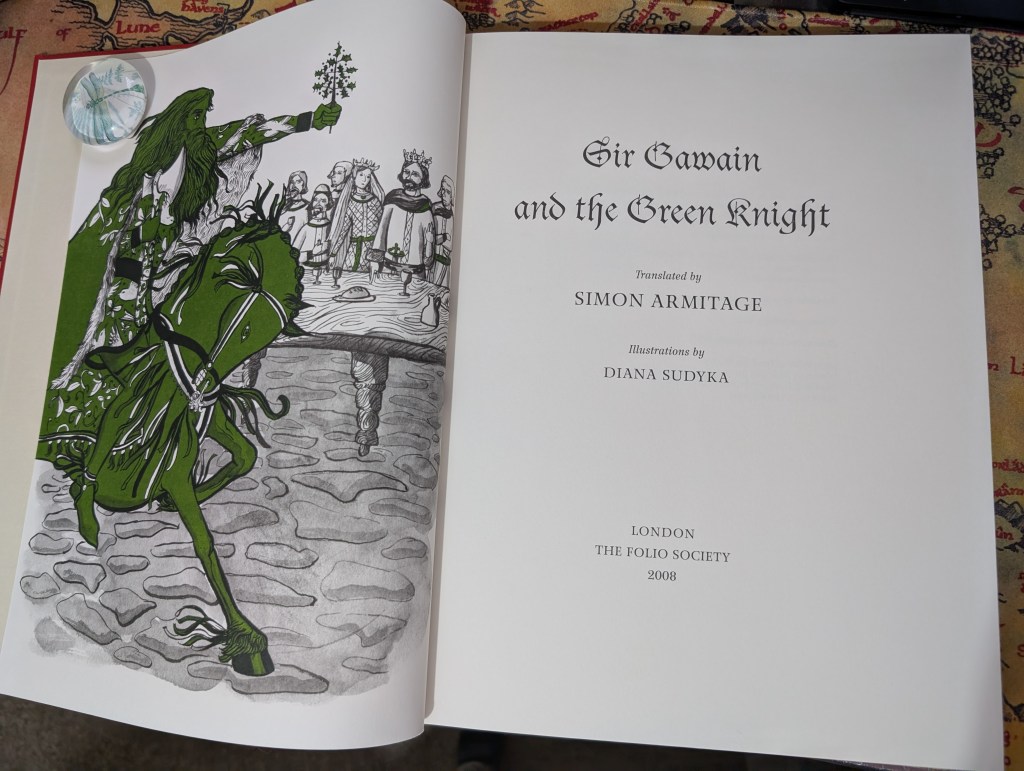

These carvings are beardless; they do not remind me much of Gawain’s Green Knight, whose account I read a little before New Year through Simon Armitage’s meaty translation. This man’s verdant hair and beard are so alliteratively depicted:

“fine flowing locks which fanned across his back,

plus a green beard growing down to his breast,

and his face-hair along with the hair of his head

was lopped in a line at elbow-length

so half his arms were gowned in green growth,

crimped at the collar, like a king’s cape.”

The poem’s author is unknown; a man or woman from the Cheshire-Staffordshire-Derbyshire border, going by the linguistic analysis, probably in the 1400s. A later voice than that of Orm, calling for the church to be built, and more northern too; the landscape it evokes is that of the roaches up in Staffordshire’s moorlands, where Lud’s Church is a plausible setting for events.

The poem is set at Christmas in ye olden times of Rome where at Camelot, Arthur’s knights are feasting, stuffing themselves. Plenty there is for all, and leisure too, boredom even creeping in as Arthur pledges:

“…to take no portion from his plate

on such a special day until a story was told:

some far-fetched yarn or outrageous fable,

the tallest of tales, yet one ringing with truth,

like the action-packed epics of old.

Or till some chancer had challenged his chosen knight,

dared him, with a lance, to lay life on the line…”

Of course the story takes this dare: into the hall comes the green knight and challenges all there to take one swing at him, and find him a year’s hence and take one swing in return. A fair exchange. Or a faery one, because of course although Gawain takes up the blow and “cleaved through the spinal cord and parted the fat and the flesh” the knight catches up his head by the hair and rides off swinging it from his fist. After lingering as long as he can at Camelot, Gawain eventually seeks his honourable appointment with death. He cheats a little though, as on the way he is hosted by the green knight in disguise and in exchanging fairly the kisses granted by the knight’s wife for the spoils of three hunts, he keeps to himself the secret gift of the lady’s girdle enwoven as it is with protections against death. The knight spares his life, but with the edge of his blade he nicks Gawain’s neck, for his cowardice.

The tale is fantastical, a ghost story that familiarises death and in some way also forgives the extremes people will go to to avoid it. A mid-winter tale for when the old year must die and birth the new, bleary-eyed in winter’s greyness. Spring is coming, but not yet, not yet. We are not out of those woods yet. It’s a story of survival, as St Chad’s church with its miraculously (and suspiciously) well preserved carvings also tells. It’s also as twisty as Orm’s wyrms as it wriggles away from simple summations. This year, it’s what I needed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.