There is no glittering frost outside today and the lengthening nights shut me in earlier and earlier. To make it through such dark hours I want comfort and enchantment, and for this I turn to the books I read over and over as a child.

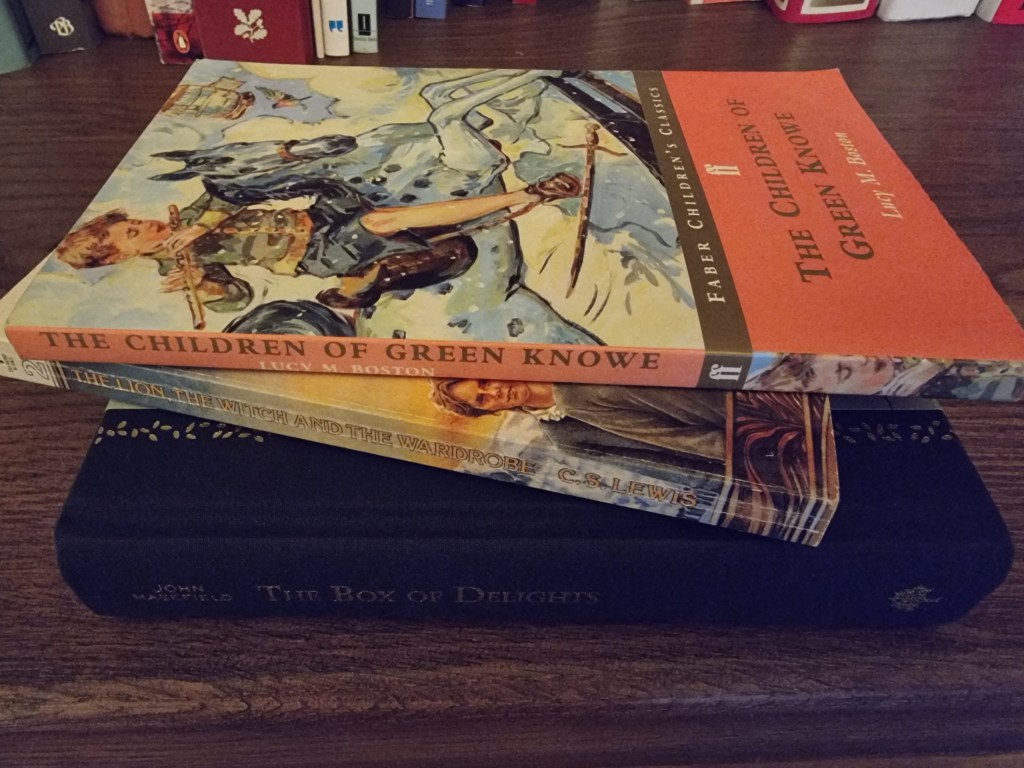

Some favourites, such as Susan Cooper’s ‘Dark is Rising,’ and John Masefield’s ‘Box of Delights’ are acknowledged public treasures, featuring in the British Library’s ‘Fantasy: Realms of the Imagination’ exhibition, which I hope to see soon. Others, such as Katherine Briggs ‘Hobberdy Dick’, are undeservedly less known. These books’ comforts have a firm grasp of the earthly, offering a reader vicarious meals of sticky marmalade pudding, buttered eggs, or even simple rolls of fresh bread, split and spread with honey, eaten standing in the snow. With food that nourishes body and spirit, readers and protagonists alike can face dangers as the stories unfold.

The books offer more than comfort eating though. They are powered by a lyricism that book jackets blurb as ‘evocative’ or ‘enchanting,’ words deriving from Latin that imply calling or singing into existence. It’s no surprise then that John Masefield is as famous a poet as he is a prose writer, or that prophecies, poems and spells feature heavily in these books.* Similarly Susan Cooper: ‘When the Dark is rising, six…’ if you’ve read this far you can probably complete that line yourself.

In my own writing I wanted to work with this lyrical tradition, and my children’s book Gemella Forever, set mainly in ancient Pompeii, includes a poem and a prophecy, both in Latin (the only Latin in the book) emphasising the gods’ alienness. Firstly, the household god, the Lar, calls on Apollo for help using a snippet of Tibullus:

‘Phoebe, faue: laus magna tibi tribuetur in uno corpore seruato restituisse duos.’

‘Bright Apollo, be gracious, great praise is your due – in saving one life you will restore two!’**

Then an important prophecy is given by Apollo, which my 9-year old heroines Scarlett and Amica must figure out if they are to escape and survive. It explains that Amica is Scarlett’s gemella, her twin, which baffles both girls. In the end however they figure it out and in fact their twinship comes down to the choices they make. They end up in contemporary London, where I can imagine them calling to each other in school, or graffitiing their desks, with ‘Gemella Forever.’

*https://ies.sas.ac.uk/masefield-society

**Only the slightly loose translation is mine; the Latin is from Tibullus’ Elegies, book 3, poem 10 and is in fact a prayer for the health of Sulpicia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.